The Bowes Museum Blog

The resurrection of a tired Friar

27 Oct 2017

Before and after conservation. The left image is before conservation, with a yellow discoloured varnish and overpaint partially hiding the paint(photo: Jason Hynes). The right image is after conservation, where the painting has been fully restored.

The conservation of the Spanish portrait of Fray José Sigüenza (B.M.17), which was mentioned in our Exposing of a Worn Painted Surface blog entry is now completed, and I can finally present the results of the restoration process.

The restoration can be divided in to three separate phases:

- Varnishing

- Filling of losses

- Retouching

In this blog post I will first present the different phases and then I will reveal an intriguing mystery regarding the Latin text painted on the picture.

Varnishing

For most historic art works that were made before the pre impressionistic era, varnishing is an obvious step in the conservation treatment. A picture varnish is traditionally a natural resin in a solvent solution applied to the painting to saturate the colours. In addition it can act as a protective layer between the paint and for instance dust, soot, smoke or minor abrasions. Because varnish layers tend to oxidize and degrade, they turn yellow and loose transparency. This sadly means that the tonal variations in the painting changes, making bright colours look discoloured whilst the darker areas look duller. Consequently, throughout the decades, there has been much effort to remove and replace varnishes on pictures in attempts to allow people to appreciate the original colours and tonalities created by the painters.

After I removed the old, discoloured varnish on Fray José Sigüenza, the painting was left with irregular matt colours and with a rather uncoherent looking surface. To compensate for this, a new varnish, that is likely to yellow less than the older natural resin varnish, was applied to re-saturate the colours. This varnish would also protect the paint film from dust and abrasions, as well as create an isolation layer between the restorations I would later apply. The new varnish comprises a modern, synthetic resin with long-term stability that is dissolved in solvents, and is applied to the painting with brush.

Varnishing proved to be challenging, firstly because the painting was absorbent, and secondly because several layers had to be applied to achieve a desired surface.

First an isolation layer was applied to isolate the paint surface from the following filling material and retouching paint.

First layer of varnish was applied with a brush as seen in the image. Later applications were done with spraying the varnish solution on to the painting.

Filling of losses

Because of the fragmented and worn looking surface exposed after the cleaning, the painting had to be aesthetically restored.

It was decided to do a complete reintegration of the losses with the aim to reconstruct the missing paint by imitating the appearance of the original paint as closely as possible by application of paint solely to areas of loss or damage in the original paint layer. By in-painting the losses and abrasions, it was hoped that the picture could be viewed without the damages being too noticeable to the viewer. This form of retouching might be considered as a form of deceptive or total re-integration, where the focus is given to the original composition and creation by the painter.

After the isolation varnish had dried, I started the process of filling the losses with acrylic putty which I later could retouch on. The filling material was applied with small spatulas or if diluted: brushes. This stage may at first not seem important compared to the other two phases of the restoration, but if the levels of the secondary materials do not match the level of the original materials, it is impossible to create an integrated retouch later on. A successful infill should not cover original paint but also needs to have a texture that resembles the surrounding original surface. The better the fillings, the better the retouch will blend in and the painting will come to life again.

Retouching

The retouching process proved to be very tedious because of all the old tears, small losses and abrasions throughout the painting. I used a modern synthetic binding medium that will not degrade as rapidly as traditional oil paint, and consequently it will be possible for future paintings conservators to remove the retouches I have added. I mixed the binding medium with pigments to create colour matches and applied this carefully with small brushes. In many places it was necessary to create layered structures to achieve a good result. After the last brush strokes of retouching paint was later applied and properly dried, a few thin layers of varnish were applied to make the surface’s gloss look coherent.

The retouching process is a long and tedious process where retouches are carefully applied to the losses. It disguises, although detectable for future paintings conservators, the damages so it is possible to enjoy the original artistic creation without disturbing white fields across the surface. Binding medium created by adding a synthetic resin to a solvent and later mixed with loose pigments as seen on the easel.

While sitting in front of the painting for lengthy hours, you often ponder whether it is possible to restore the painting to its former glory? In some ways it is not. Time is brutal thing for paintings and the paint. Since Fray José Sigüenza left the hands of its creator, it has chemically changed and this has among other things has altered the transparency of the paint medium and is also likely to have affected some of the pigments. Physical losses and abrasions have also happened in the 400 years since the creation. The in-painting was therefore matched to the state of the paint at the time of retouching and not how it might have looked at the point of completion. Therefore I see restoration of paintings as a way to respect the history of the object, and I would argue that the painting now is more authentic and true to the original creation, most likely by Bartolomé Carducho (1560-1608).

A philological mystery

As previously mentioned Latin text was originally painted on the picture but for unknown reasons hidden beneath layers of overpaint. A photo by Eljiah Yeoman(1998.17.97/ARC) from the late 19th century proves that during early ears of display at the Bowes Museum, the Latin text was overpainted. At some point, someone tried to remove the over paint, but as written records are inconclusive it is not possible to say when. In January 2017 the painting was taken out of the Picture Store in the state as seen in the first photo.

A cropped original photo by Eljiah Yeoman (1998.17.97/ARC) shows the painting Fray José Sigüenzaon display in the main Picture Galleries without the writing.

Top picture shows the state of the top part of the painting before conservation with previously partially removed overpaint and varnish. Bear in mind that the picture was brought from the depth of the picture store at the museum where it had been left for a long time, possibly because the cleaning of the painting had proved to be tricky. Middle image shows the cleaned state, with all varnish and overpaint carefully removed. Bottom image show the final result of the restoration.

The Latin script is as follows:

VERA EFFIGIES RR. P. M. F. JOSEPH DE SINGUENZA, HUJUS R.

COENOBII FILII ET COENOBIARCHÆ

Tanta Tibiprobitas, linguarumcopiatanta,

Maximus utnobis jam videareParens.

Thanks to colleagues, it is possible to present to you the meaning of the text. It proved to be difficult to translate, but if you have other suggestions, please leave a comment in the comment section below or email the museum.

The meaning of the text proved to be a statement of who the sitter is, and it translates to:

The true image of Reverend Father Master Fray Joseph de Siguenza, son of this monastery and abbot

So much honesty to you [you have so much honest], and such abundance of language, that to us already you seem a great father

To make the Latin text even more mysterious, the third line had two different layers. After careful examination under low level magnification I discovered fragments of the first layer and that it ultimately stated the same as the second layer, although shifted towards the centre to make it symmetrical compared to the three other lines, and two commas had been added to separate the sentence into three subordinate clauses.

Top image shows the bottom Latin text before conservation. Middle image is after the removal of discoloured varnish and old retouch, but before varnishing. Please notice the double layer of writing in the first line. Bottom image shows the Latin text after restoration

Based on the observations I did during the investigations and treatment, I strongly believe it was the same artist that covered the first line of letters, shifting it to the right as to make it more symmetrical with the other lines. I believe this because of visual observations of the materials in the paint and the technique is so similar that it most likely is not a later addition. We did then consider the first layer of script to be a form of pentimenti, a deliberate change of compositions by artists that may later become visible, but was not meant to be seen. After several discussions, I did cover the first layer by an inert, synthetic and reversible retouching overpaint. The decision was influenced by the final aesthetics of the painting and the public’s ability to read the image and text. The treatment was carefully documented. The fact that there are two layers of writing might be of significance, as some pentimenti can be considered especially important when deciding whether a particular painting is the first version by the original artist or a second version by the artist himself, his workshop or a later copyist.

One can speculate that compared to the other version of the painting that remains in El Escorial outside Madrid, where Sigüenza lived and worked, this painting, due to the writing was supposed to be transported to other locations. If so, it is awesome that the painting has managed to travel to the north-eastern English countryside, where it will be presented at the Museum in the Picture Galleries and can be enjoyed by the public for years to come.

Final reflections

Based on all the observations and evidences that we collected during treatment, we strongly believe that we now can present you with a painting which is possibly more true to the original aesthetic creation that the artist made more than 400 years ago. This is a consequence of the removal of the discoloured varnish and old retouches, and then replacing with new, lightfast varnishes and retouches. I feel privileged to have been able to spend so much time in front of the painting, possibly even more time than the artist himself did. I feel humble for the interventions I had to do. I feel happy to present the result, with all the resources available in mind. The ultimate aim of a paintings conservator is to do as little as possible; at least to such an extent that one does not interfere with the aesthetic. It might be possible to think of the visual re-integration like revitalization, what once was a tired looking picture is again ready to serve as a painting for many years to come. The friar is no longer tired, and is ready to serve as a proper painting for years to come.

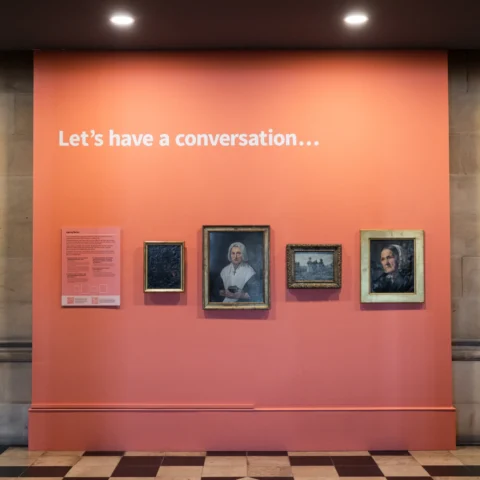

Tor Skaaland in the gallery with the restored Fray José Sigüenza