The Bowes Museum Blog

The Silver Swan Story

Initially, made to impress emperors and their visitors, the fantastic Silver Swan had a bit of an adventure before joining The Bowes Museum’s collection and enchanting everyone that visits the Museum.

The Silver Swan was first recorded in 1774 as a crowd puller in the Mechanical Museum of James Cox, a London jeweller and 18th century entrepreneur. The internal mechanism designed by John Joseph Merlin, a famous inventor of the time, is an intricate clock like mechanism that powers the delicate movements of the Swan’s neck. James Cox was so acclaimed after making the Silver Swan, that he was asked by the Russian court to create a bespoke automaton to adorn their parties. Hence, the famous Peacock Clock, now hosted by the Hermitage Museum, was created.

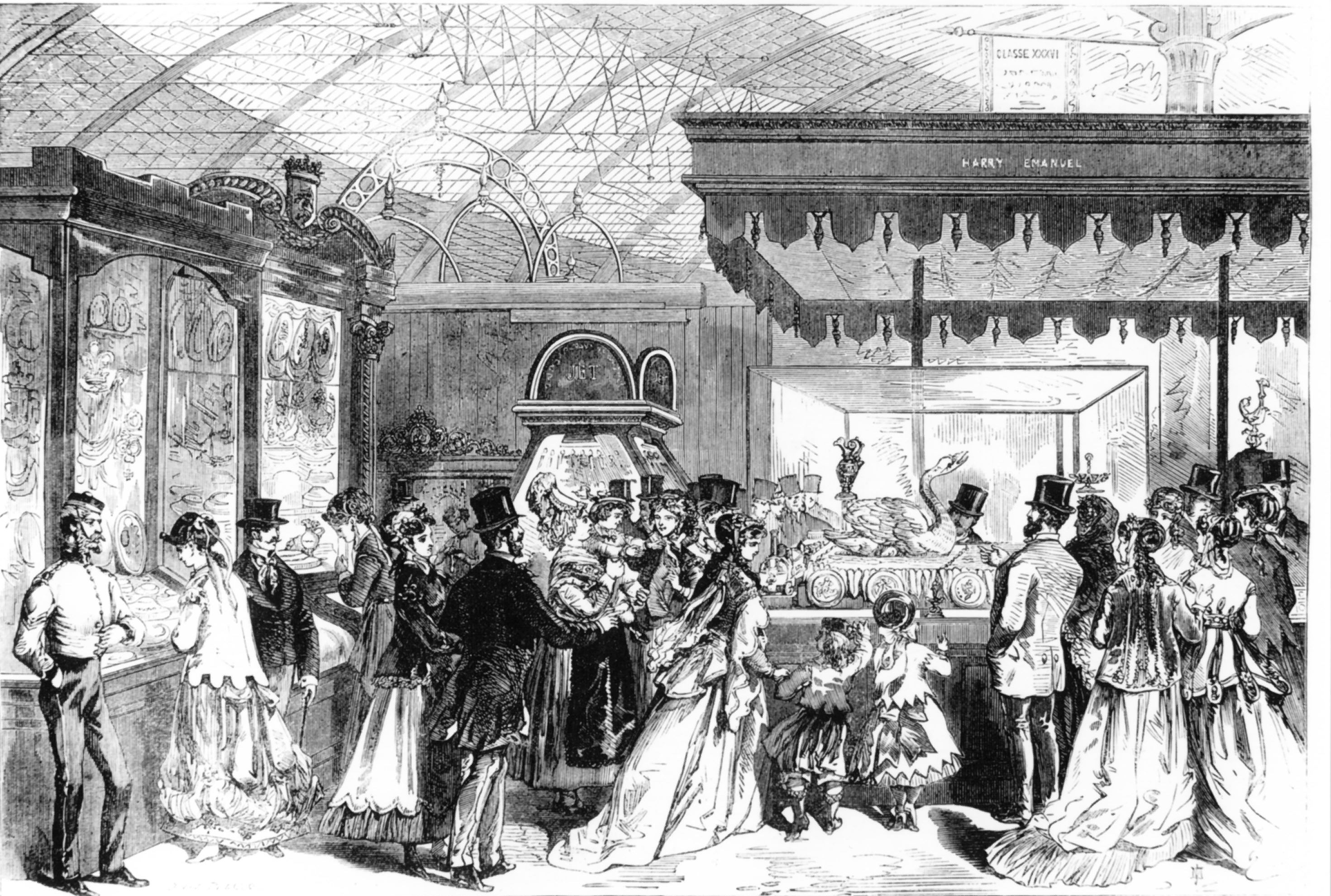

The beautiful Silver Swan has a similar story, it was demanded by royalty that ended up changing their minds. The Swan never sailed away to faraway lands, remaining in the UK to be exhibited in the ‘Spring Garden’, James Cox’s curiosities museum. In mid 19th century, jeweller Harry Emanuel, who must have been in the possession of the Silver Swan at the time, exhibited it in the famous Paris International Exhibition.

Drawing of the Silver Swan at the Paris International Exhibition

The Paris International Exhibition or Exposition universelle [d’art et d’industrie] de 1867 was the talk of the town at the time. With over 40 nations exhibiting rare, interesting and innovative objects and receiving visitors of royal descent from all over the world, it was the place to be. As avid collectors but also socialites, the Museum’s founders Joséphine and John attended the exhibition as well. This is where they saw the mechanical Silver Swan in 1867 and fell in love with it.

And they were not the only ones!

The American novelist Mark Twain also saw the Silver Swan at the Paris exhibition in 1867 and described it in his book The Innocents Abroad:

‘I watched the Silver Swan, which had a living grace about his movement and a living intelligence in his eyes – watched him swimming about as comfortably and unconcernedly as it he had been born in a morass instead of a jeweller’s shop – watched him seize a silver fish from under the water and hold up his head and go through the customary and elaborate motions of swallowing it…’

Joséphine and John Bowes contacted the seller, a Parisian jeweller called M. Briquet, and John paid £200 (approx. £20,000 today) for the Silver Swan in 1872, a great steal for such a remarkable and rare object.

Besides being charmed by the beauty of the Silver Swan, staff at the Museum like to think this purchase was also influenced by Joséphine’s childhood. Her father was a clock-maker and she had a fondness for automata.

Whilst the Silver Swan is the best known, there are a number of others including mechanical toys, music boxes and watches with automaton movements at The Bowes Museum. Examples include an early 17th century lion clock made in Germany whose eyes swivel, and a mechanical gold mouse adorned with pearls, circa 1810, which is probably Swiss.

What happened to the Silver Swan once it was bought?

The Silver Swan had been on display as a static object since The Bowes Museum opened in 1892, save for a period during World War II when it was believed to have been dismantled and packed away for safety. It was restored to working order by one of the Museum attendants in the late 1940s, and soon became its most popular attraction.

In the 1960s it was known to have undergone conservation and restoration on three separate occasions [twice in London]. From the time of the latest of these, in about 1968, it has been in almost constant demand to ‘perform’ regularly for visitors to the Museum.

In 2008 the first major conservation project was conducted in a generation; its purpose was to strip the mechanism and thoroughly clean and record every component. The work was undertaken by Matthew Read, a clockmaker and conservator.

Read here about the maintenance of the Silver Swan.

At the same time, the Museum commissioned two historians, Roger Smith and John Martin Robinson, to research the history of the Swan and its makers. The results of both projects have been made public in the pages of Country Life magazine (13th May 2009) and in a multimedia interactive presentation in the Silver and Metals Gallery in the Museum.

The Silver Swan stopped working during the covid pandemic, when the Museum was temporarily closed to the public.

It was then the subject to a two week study period in 2021, when it was taken apart again by a team of expert horologists and conservators, led by Matthew Read, and a concise record was taken of what work it would need to get it running again.

That work was carried out in 2023, into 2024, when the Museum received funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund and also surpassed its target during a crowdfunding campaign. Members of the Cumbria Clock Company, supported by the Museum’s conservation specialists and horological experts as well as interns from clockmaking courses, spent more than 1,500 painstaking hours restoring and repairing the intricate iconic object.

The Silver Swan is now back performing everyday at 2pm, with an extra performance at 11.45am during school holidays and on bank holidays.

The Bowes Museum is extremely proud and honoured to have such a beautiful object in its collection, a true 18th century robot that delights everyone with every graceful move.

By Leo Rotaru, Marketing Assistant