The Silver Swan

The Paris International Exhibition (1867) and its 50,000 exhibitors presented a supermarket of delights for its millions of visitors. One star of the show was the Silver Swan which charmed viewers with its lifelike movements – preening and feeding – as they marvelled at its price tag of 50,000 francs . Five years later, a French jeweller, Monsieur Briquet, alerted John Bowes that the swan was for sale and eventually, in 1873, it was bought for only 5,000 francs (£200).

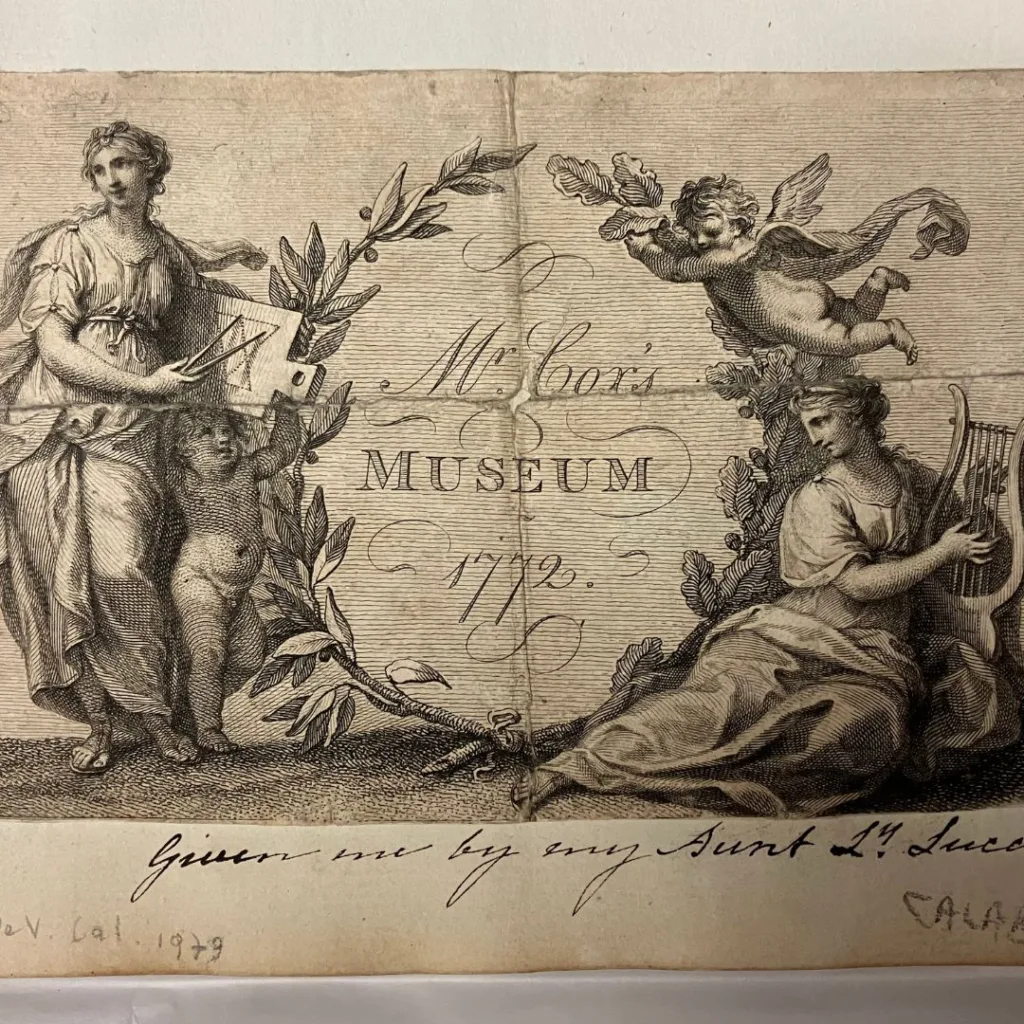

The Swan’s story began in 1773 in the London workshop and mechanical museum of James Cox. Though he is known as a jeweller and goldsmith, Cox was more showman and entrepreneur who employed craftsmen to bring his ideas to life. Ornately decorated musical curios were sold to customers in the Far East, particularly India and China. It is thought that the Swan was destined for Emperor Qianlong of China, who owned a chariot automaton bought from Cox, but he changed his mind before delivery.

It’s a lifesize replica of a female swan containing 2,000 moving parts, including 139 crystal rods, and 113 neck rings. Three clockwork mechanisms: one for the shimmering pool of glass with swimming silver fish; one for the musical tunes and one for the complex mechanism controlling the swan’s head and neck. The latter was the genius creation of John Joseph Merlin who worked for Cox.

Daily performances ceased during lockdowns and the automaton was in need of some ‘tender loving care’. Now in its 251st year, The Bowes Museum is thrilled that this magnificent object has been brought back to working order after more than 1500 hours of painstaking work carried out by experts at the Cumbria Clock Company, assisted by specialist horologists, clock interns from West Dean College and Birmingham School of Jewellery as well as the Museum’s in house conservation team. The Silver Swan is once again wowing audiences with its daily 2pm performance with an extra one at 11.45am during school holidays and bank holidays.